On Making Decisions Under Uncertainty

COVID-19 has stalled many aspects of our lives. Social events, extracurricular activities, travel plans, etc. Perhaps it has stalled even bigger things like buying a house, or a car, or choosing between university programs. Although we are hopeful that eventually the virus will be bested and we will be able to pick up where we left off, right now, we’re not sure how this situation will turn out, when the isolation orders will lift, or even what our new normal will look like. How do we go about making decisions about our lives with these insanely high levels of uncertainty? And in some cases, without ever being able to try before you buy?

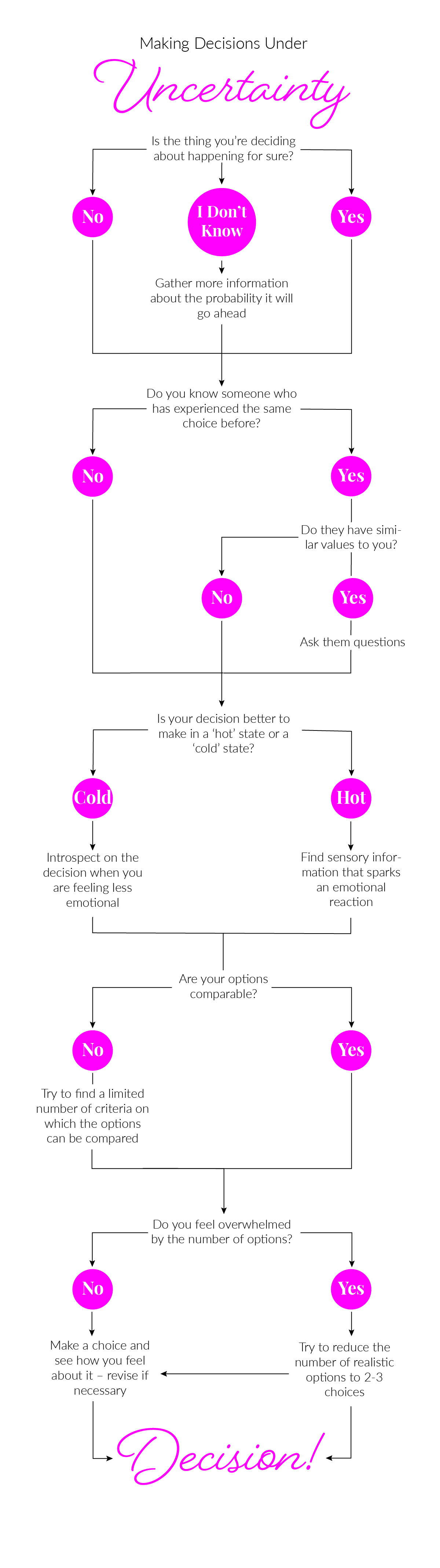

It comes down to gathering more information (but only the right kind!), getting into the right headspace, and narrowing down the options.

Making Decisions is Hard

Wait, or is it? We make a zillion tiny decisions every day and think nothing of it. Think about it. You decide to turn off your alarm, get up, get dressed, lock your door, when to cross the street, to hold on to the pole in the subway when it starts to get bumpy, etc. On the other hand, some decisions are crippling, like whether or not you are going to put in an offer on that house, what to say in your big presentation, and – toughest of all – what to have for dinner tonight.

To having takeout for dinner… and beyond!

Some decisions are made very easy because of heuristics, the mental shortcuts that allow people to make decisions quickly and effectively in a way that reduces mental effort.

However, making decisions under uncertainty is much harder because:

When thing are uncertain, we tend to think more inflexibly;

We put more weight on what others are doing, causing us to act in a conformist way;

We may be feeling different emotions than those under which we would normally make big decisions (thanks for that crippling anxiety, uncertainty!!!);

Uncertainty can mean lack of familiarity with a certain decision, which leads to more cognitive energy to try to figure it out, which might lead to us not making any decision at all.

Many of our decisions have an element of uncertainty as we can’t possibly fully know the true underlying quality (or the suitability for us) of the thing we are committing to, and sometimes the seller - wanting to make a sale - might be unwilling to tell us the cons alongside the pros. For example, even test-driving a car, it still might end up being a lemon. This is a key premise of the Theory of Asymmetric Information, which refers to a situation where one party in an economic transaction knows more than the other person (usually the seller knowing more than the buyer). But testing out that car reduces the uncertainty in some capacity, which is why trying before you buy is so popular in many economic transactions (who doesn’t love free samples!).

But now in COVID-19 we have some extra uncertainty thrown into the mix thanks to a new and complex public health emergency. Extra decision-making uncertainty now comes from not being able to test or try stuff out (ex. clothes, beauty products, even our participation in sports teams), not seeing things in person (ex. a new apartment, a new kitchen appliance), and uncertainty about our own health and livelihood (ex. temporary unemployment, or fears about you or a loved one contracting COVID-19).

We all hope we will be able to resume our lives and at least some of our activities in the coming months. But in the meantime, how do we make decisions under so much uncertainty? Here are some top tips (and a really cool decision map at the very end!):

1. Gather More (Relevant) Data

So I want to join The Falcons sports team in the fall, but I’m not totally sure I’m going to enjoy it. Normally I’d get the chance to participate in an open house to see if I like the team culture. Should I commit to the team anyway?

What will help here is to gather more relevant data.

Feasibility – is this thing going ahead?

The first thing to check is if the thing you are deciding about is even happening at all. If the organizers (or sellers, or employers - in the case of a new job) are still unsure (ex. with skating, we’re not sure when the rinks will re-open), ask for a ballpark estimate of the chance the program will go ahead, or their plans in response to certain scenarios like facilities being closed longer than predicted or a continued hiring freeze.

Acquire Reviews – but specifically from a like-minded source.

We are highly influenced by the decisions and opinions of others – and in our digitized world, this frequently takes the form of online ratings and reviews about products and services. Different than having the ability to experience before committing in person, reviews play a crucial role in providing information about a product or service as experienced by someone else. We are so swayed by reviews that studies have found people will still look up online reviews even after they have received a recommendation about a product or service from a friend or family member.

Reviews can be problematic, however. There are many reasons why public online reviews might not be accurate. People who write reviews tend to be in a heightened emotional state (positive or negative!) and are more likely to write negative reviews than positive ones; people might be self-promoting, looking to stroke their ego and look like an expert, and 20% of reviews originate from a feeling of vengeance. Additionally, is the writer of the review evaluating the product or experience based on the same things that you would appreciate? How would you be able to tell if you will be happy if you make this decision? 91% of people regularly or occasionally read online reviews, so we had better figure this out!

Find someone who’s similar to you and ask them for their review.

I suggest finding someone who has had experience with the choice you’re trying to make, and is similar enough to you in their values, to offer up key points about the experience as a proxy for how you would likely experience the outcome of the decision too. Looking to join a sports team? Find someone who has the same athletic background or works a similar job to you to see how you will manage this commitment. Looking to buy a house? Is there someone similar to you in the neighborhood who can speak to what life is like there on a summer weekend?

Gathering information from similar people can help decision making

2. Get in the Right Headspace

I know we like to think of ourselves as rational decision-makers, but the reality is that we (especially as consumers) are of the emotional variety as well. Trying things out before we commit to them is important, not only because it gives us clues to the ‘true’ underlying quality, but causes an emotional reaction in us that helps us to make our decision. Without that emotional input, the decision might feel harder.

STORY: Emotions play greatly into our decision-making. I hear stories from my figure skating friends about how they intend to make a certain season their last one before retirement. The late nights at the rink, the cost of the season, friction with teammates, driving in snowstorms, missing other social events, etc. The time to make a decision is right after our National Championships, the highlight of the year! Everyone has had so much fun together, and this sensation of fun and belonging signs everyone back up again. Why? It’s called Peak-End Rule, when the memory of an experience doesn’t correspond to the average positive or negative level of the experience, but more to the emotional peak of the experience or the end of the experience. So the high we experience at the end of the season factors overwhelmingly into coming back again the next year. And we rely very heavily on those emotions to make a decision.

Making Decisions in a Hot State vs a Cold State

The Empathy gap is the tendency to underestimate how the state of our emotions impacts decisions and behaviours. Being in a ‘hot’ state is when you are impacted by emotions (sad, angry, etc.), and being in a ‘cold’ state is tapping into rational thought. This gap can totally derail our plans. Take the example of dieting. We often make our diet decisions in a ‘cold’ state, but fail to resist junk food in a ‘hot’ state.

Research has tended to focus on how the Empathy gap leads to bad decision-making, but the reality is that we rely on our emotions to help us through a lot of decisions. In fact, marketers believe that we make emotional decisions and rational justifications.

Now that we are restricted in our ability to ‘test’ and ‘experience’ things before making a decision, we might be making that decision in a colder or different emotional state than we otherwise would be. For example, I had a strict list of criteria when I was looking to buy a house, and the one I bought didn’t match those criteria but I fell in love with it – and I likely would not have bought this house without the emotional inputs (but I’m so happy I did!!!). Additionally, often the feeling of being out of control that comes with uncertainty (i.e. due to COVID-19) leads to negative emotions. So instead of maybe feeling optimistic and having fun at a figure skating tryout, you’re sitting at home worrying about COVID-19, and thinking about never leaving the house again.

What Will Allow You To Make a Better Decision?

Do you need that emotional input or will you make a better decision in a rational, ‘cold’ state? Perhaps making the decision in a cold state will stop you from making a rash or impulsive decision.

Tap into Your Senses.

What proxies do you have around you that will remind you of the experience? Pictures, videos, digging out old skating dresses, booking a Zoom chat with the ski team, get mailed a sample of that expensive face cream, etc. You will be more likely to get the emotional information you need if you access sensory artefacts that heighten that information.

We’re not as rational as we think we are

3. Reduce the Number of Options

Many would agree that having more options is desirable; it gives the sense that we’ll be able to find more precisely what we want from the different options.

However, more choice is not necessarily better, and having too many choice options (or too much information to consider) can grind decision-making to a halt. This is known as choice paralysis. Having too many choices has also been shown to reduce our satisfaction with a choice.

This is why we humans tend towards routines. Routines diminish the amount of cognitive load on our brains and rely on pre-existing patterns. The familiarity of the choice or behaviour feels easy.

Having more choices increases time and effort, potentially leading to anxiety, which clouds your judgement and you might feel like you have less control. And in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is certainly common to feel like we currently have less control.

Avoid choice paralysis by narrowing down options

Is there any way you can let go of some of the options? Reducing the number of options might get you un-stuck in your decision-making. Also, we have a much easier time comparing apples to apples. Try finding common criteria between options to make the choice easier to process.

Beware the Sunk Cost Fallacy.

We tend to commit to choices in which we’ve already invested some time, money, or effort, even if they don’t make sense anymore. Give yourself permission to say goodbye to some ideas if they aren’t working for you in our “new normal” paradigm. Going forwards, have criteria for a cutoff point that’s a less subjective marker of ‘what’s working for you right now’.

Increase Subjective Feelings of Control.

Much anxiety about making a decision is related to the sense that we don’t have control over the decision. What’s worse, we are naturally inclined to allow spillover from one source of uncertainty to another, increasing our sensitivity to this sense that we lack control. It may be possible that the uncertainty surrounding what will come of the COVID-19 pandemic is spilling over to your other decisions too.

Check Yourself. Is the uncertainty you’re feeling from COVID-19 spilling over to your decision-making? Narrow your thinking to just the question at hand.

Not a good strategy!

(BONUS!) Are You Trying To Get Someone to Commit?

Reduce the risk by giving people an ‘opt out’ period. People are more risk averse when it comes to losses – and with more uncertainty and destabilization comes the perception that the decision will more likely end in a loss. Reduce that loss aversion by reducing the risk. Provide your target group an option to opt out without cost (or reduced cost). Ex. Sign up for gymnastics now! We’ll give you your money back if we can’t re-open before July 1st.

Provide commitment levels, giving people the choice to pick the option that suits them best right now. Ex. I can commit to one night of practice a week in the fall right now, and might be able to commit to 3 nights of training a week if things stabilize by August.

Provide access to more information. Maybe you have people on your team you can connect to newcomers to answer questions. Send videos, pictures, etc. to show them what the experience will be like.

It’s difficult to make plans when the state of the world is changing so rapidly from one day to the next, but with the right decision-making plan, you have a better chance of knowing what you want and going after it. Here is our master decision-making map!

I choose you, Friend!

Love,